On Sunday, June 19, our nation will celebrate Juneteenth, which commemorates the abolition of slavery, as a federal holiday for the second time.

Unlike many holidays, Juneteenth was created by working people — specifically, by formerly enslaved Black people following the Civil War. It celebrates emancipation from forced labor, a victory won in no small measure by a “general strike” of the enslaved.

Juneteenth is an opportunity to reflect on the ways that the history of slavery still shapes our country’s politics and economy. It is also a reminder of how our history — including the history of all labor struggles — is shaped by the conflict between our human desire for freedom and our bosses’ demand to control our labor.

Proclamations and General Strikes

The emancipation of enslaved people in the U.S. was not a straightforward process. Although the Southern states that seceded from the Union and began the Civil War clearly did so in order to preserve the institution of slavery, President Lincoln and most political leaders in the North initially claimed that the sole purpose of the war was to “preserve the Union.” (Indeed, the “border states” of Maryland and Kentucky remained in the Union, yet were permitted to maintain the practice of human bondage.)

Black people thought otherwise. Close to 200,000 Black men — both free Blacks from the North and enslaved Blacks from the South fleeing the homes and plantations they worked on — enlisted in the U.S. Army and Navy to fight what they saw as a war for freedom.

Many working people in the North, especially trade unionists, also understood the war to be about slavery. As Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais wrote in Labor’s Untold Story, “When President Lincoln called for volunteers the entire membership of trade union locals enlisted in single groups, knowing well that there would be no free trade union movement if the slaveholders triumphed. … Entire companies of Illinois volunteers were composed almost exclusively of members of the Miners’ Union and in Brooklyn the Painters’ Union resolved to fight as a unit against the slaveholders’ conspiracy.”

This pressure from below forced Lincoln’s hand, and on September 22, 1862 (over a year into the war) he issued the famous “Emancipation Proclamation,” declaring all slaves in the Confererate states to be free, effective on January 1, 1863. Notably, this proclamation did not free slaves in the border states, and, especially at that point in the war, the U.S. government had virtually no authority over the Confederate states.

Nonetheless, the proclamation effectively recast the Union’s war aims as being the abolition of slavery, and it increased the flood of enslaved people leaving the plantations, workshops and homes of the South to join the Union cause. Historian W.E.B. DuBois, in his work Black Reconstruction, attributed the Union’s victory to this “general strike against slavery,” which both swelled the ranks of the Union army and, crucially, deprived the Confederacy of the labor needed to maintain the war effort.

On January 31, 1865, Congress passed the 13th Amendment, abolishing the institution of slavery throughout the country (it would be ratified by December), and the Confederacy officially surrendered on April 9. However, word traveled slowly and slave owners in Texas, where many had fled to escape the Union armies, were not keen to inform their enslaved workers that they were now free. Thus it was that Major General Gordon Granger of the Union army felt the need to issue a proclamation on June 19 in Galveston, Texas:

The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves…

Juneteenth celebration, 1900 (public domain)

The following year, Black people in Texas gathered on June 19 to celebrate their freedom as “Jubilee Day,” named for a passage in the Biblical book of Leviticus describing a time when slaves and prisoners were to be freed, and debts forgiven. Early celebrations focused on registering voters. The participation of newly-enfranchised Black voters in the “Reconstruction” governments following the Civil War led to many advances, securing the first real public education systems in the South, fairer taxation, and the election of 16 Black men to Congress.

No longer tied to a particular place by the institution of slavery, Black people in the South began to travel, and the celebration of Juneteenth spread from Texas throughout the South. In the 20th Century, the “Great Migration” of six million Black people from the South to the North, Midwest and West brought Juneteenth to the whole country.

Valued Above All for Their Labor

However, as historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote in The Root in 2013, “with each new slight, with each new segregation law, with each new textbook whitewashing and brutal lynching in the South, African Americans felt increasingly disconnected from their history, so that by the time World War II shook the nation, they could no longer faithfully celebrate freedom in a land that still rendered them second-class citizens.”

Black Americans were hardly emancipated from slavery into freedom — as Granger himself made clear in his proclamation, which, immediately after its invocation of “absolute equality,” continues:

… the connection heretofore existing between [former masters and slaves] becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Rebecca Dixon, the executive director of the National Employment Law Project, explains, “The master became the employer and the shameless insistence that ‘idleness will not be tolerated’ was an only slightly veiled hint that social control and surveillance would prevail in the new social structure – and that Black people would still be valued above all for their labor.”

This transition from slavery to “hired labor” was, at times, enforced violently — especially after Federal troops left the South and Reconstruction ended.

Throughout most of the South, the plantation system was replaced with sharecropping — a system in which Black (and some poor white) agricultural laborers worked on land belonging to former slave owners, in exchange for a share of the harvest. Jim Crow laws maintained social segregation, and poll taxes (a tax that one had to pay in order to be able to vote) ensured that cash-poor sharecroppers, both Black and white, had no voice in government. In this system, Black workers, although free, continued to perform backbreaking labor to enrich a few wealthy white employers.

When Black workers left the South for other parts of the country, they were usually consigned to the dirtiest, hardest, and least desirable jobs by employers. They faced prejudice from white workers (who would sometimes strike to protest having to work with Black workers) and, shamefully, official exclusion from many craft unions. Discrimination against Black workers helped employers in two ways: it kept the working class divided, and allowed bosses to pay Black workers extremely low wages, making even more money off of their labor.

Solidarity Day

While Juneteenth celebrations may have been fading during the middle of the 20th century, the struggle for freedom was not. The 1930s saw the explosive growth of the industrial unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) — including UE. The new CIO unions, as described in the preamble to the UE constitution, sought to unite “all workers on an industrial basis … regardless of craft, age, sex, nationality, race, creed, or political beliefs.” In the South, tobacco workers in North Carolina and iron ore miners in Alabama built powerful interracial unions in the 1930s and 40s that not only challenged discrimination in the workplace, but in the political arena, registering Black workers to vote and mobilizing them to participate in elections.

And, of course, the 1950s saw the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement which brought an end to poll taxes and most forms of legal (“de jure”) segregation.

But even as the laws that maintained formal racial segregation were overturned or repealed, “de facto” (“in fact”) segregation was still the rule in workplaces and communities throughout the country. The movement’s most visible leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., came to see that the laws and policies that kept working-class Black people working for low wages, living in substandard housing and shut out of political decision-making affected working-class and poor people regardless of race, and at the end of 1967, King announced a new “Poor People’s Campaign,” which would fight for economic justice for all.

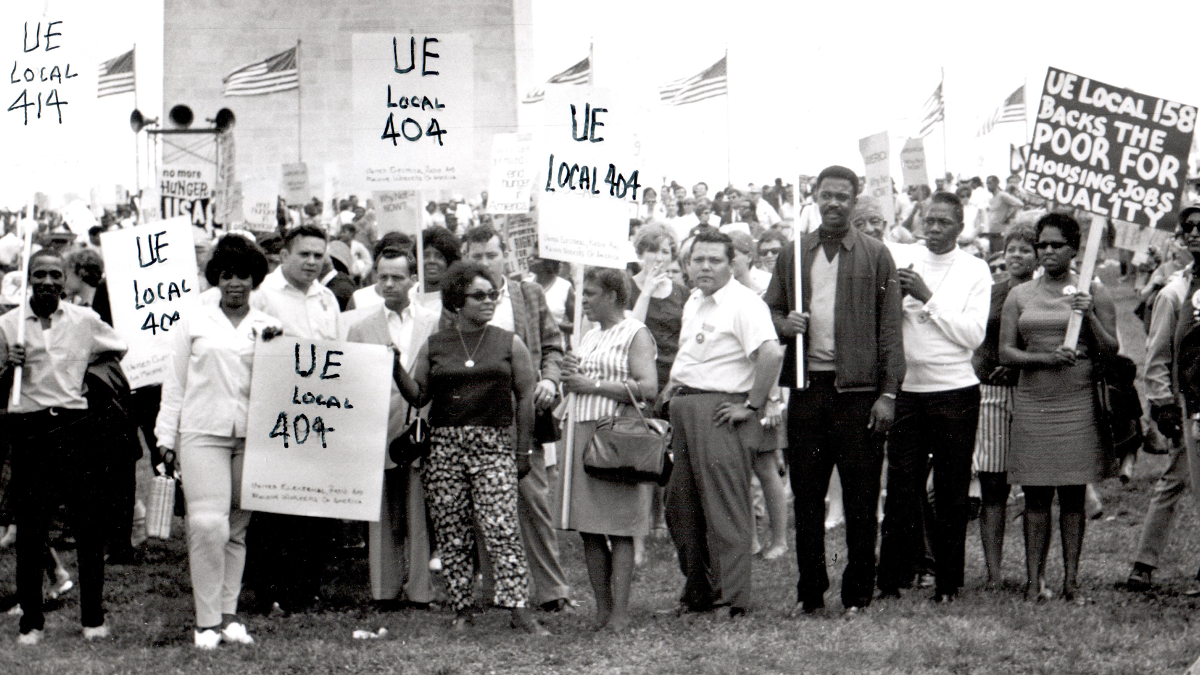

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, while supporting striking municipal workers in Memphis, but his widow Coretta Scott King and his close associate Rev. Ralph Abernathy went ahead with plans for the Poor People’s Campaign. The campaign brought thousands of people to a “Resurrection City” encampment in Washington, DC — and on June 19, 50,000 people joined them for “Solidarity Day,” a Juneteenth rally to demand “jobs, peace and freedom.”

UE members at the 1968 Solidarity Day rally on Juneteenth.

William Wiggins Jr., an Indiana University professor and author of Jubilation: African-American Celebrations in the Southeast, told Smithsonian Magazine in 2009 that the Solidarity Day celebration was instrumental in reviving the Juneteenth celebration outside of Texas:

My theory is that these delegates for the summer took that idea of the celebration back to their respective communities. So I know, for example, there was one in Milwaukee, and looking at the newspapers after that summer, they started having regular Juneteenth celebrations. The Chicago Defender had an editorial that it should be a regular idea. My feeling is that because it was used to close the Poor Peoples Campaign that the idea and so forth was taken back by different participants in that march and it took root around the country. It has taken on a life of its own.

Like Solidarity Day, Juneteenth celebrations began not only to commemorate the end of slavery, but also to raise demands for justice in the present. In 2001, UE Local 150 joined forces with Black Workers for Justice and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee to sponsor a Juneteenth march through Raleigh, NC, and a rally outside the state capitol. The march and rally celebrated the unity of Black and Latino workers in “a new movement for justice in the South,” demanding an end to racial profiling, amnesty for undocumented workers, a living wage and union rights for all. Delegates to the UE District One council meeting held in Raleigh that weekend joined the march and rally, and Director of Organization Bob Kingsley addressed the rally.

UE members at a June 2001 Juneteenth march in Raleigh, NC. UE Director of Organization Bob Kingsley is in the center in sunglasses and tie; UE Local 150 President Barbara Prear is at the right, in UE t-shirt.

Recognition and Renewed Struggle

Juneteenth was first recognized as an official government holiday by the state of Texas in 1980, and over the following decades was adopted by more and more states, responding to pressure from Black people and their allies. By 2021, all fifty states and the federal government had recognized the holiday, and New York City Mayor Eric Adams declared it a city holiday in April of this year, making it a paid holiday for city workers.

Following the police murder of George Floyd in May of 2020, Juneteenth became a rallying point for the Black Lives Matter movement. Rallies were held throughout the country, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union shut down the ports on the West Coast for eight hours. Other unions, including UE, encouraged members to “take a knee” for eight minutes and forty-six seconds (the length of time Floyd was held down by a police officer) at work.

Juneteenth played a role in one of the most dramatic labor struggles of the past year — the April 2022 victory of the independent, worker-led Amazon Labor Union. One of the first demands raised by the ALU as they began their organizing was that Amazon recognize Juneteenth as a paid holiday. Amazon, unsurprisingly, refused, but the ALU continues to make the demand.

This Juneteenth weekend, UE members will be joining the new Poor People’s Campaign led by Rev. Dr. William Barber II, a long-time UE ally, for a Moral March on Washington and to the Polls. The assembly and march will be held in Washington, DC., site of the 1968 Solidarity Day rally, demanding a $15 minimum wage and adequate incomes for all, expanded and protected voting rights, healthcare and housing for all, and more.

UE locals have also been negotiating Juneteenth as a holiday in union contracts, including, most recently, Local 329, who will receive Juneteenth as an additional paid holiday beginning in 2023.

Juneteenth: Part of the Long-Term Fight for Labor Justice

Dixon, the National Employment Law Project director, writes that “Juneteenth deserves an honored place in our labor history timeline – and it requires that we connect it to the long-term fight for labor justice, centering Black workers.”

“Juneteenth is a holiday that all union members should celebrate,” said UE General President Carl Rosen. “It commemorates the liberation of millions of our fellow workers from slavery — a system that was, above all, about controlling workers and extracting as much labor from them as possible to enrich a few wealthy slave owners.

“I encourage all UE members to find a Juneteenth celebration in their community and attend with UE gear and, if appropriate, flags and banners, to demonstrate that our union stands firmly on the side of racial justice.”

Angaza Laughinghouse, Local 150, provided valuable assistance in researching this article.