Preparing for and Conducting a Strike: A UE Guide

A strike is always our last resort. As UE members we know that there are hundreds of ways to put pressure on an employer to settle a good contract. But the strike — or the threat of one — remains the single most powerful inducement to force employers to deal with the demands of workers. Because of this, every Local — even one that has never gone on strike — must keep its strike machinery well-oiled. Remember - only your local membership can decide to strike - not UE Officers, staff or workers from other locals or shops.

A strike is the acid test of a Local. It tests a Local's ability to confront the Company. During a strike, a Local also tests itself. A poorly-organized strike can leave resentments that will take a long time to heal, even if the strike itself has been a success. A well-organized strike, on the other hand, can bring a Local much closer together.

A strike cannot be prepared for overnight. Strike preparations should gradually build up over the months before the contract deadline. This is very important. How seriously the Company takes the Local's demands will be influenced by the unity and strength these preparations show. Whatever else they might think, the Company should never be given a reason to believe the workers are bluffing.

Furthermore, some strike activities are part of what every Local should do, day in and day out. The most important is mobilizing the membership. That means the entire membership must be drawn into strike work and kept fully informed at all times. Contact between strikers and strike headquarters must be maintained throughout the strike. All members of the Local should be given every opportunity to participate fully in the strike leadership and activities. That is what a strike requires. But if a Local is already working to keep its members active and mobilized, gearing up for a strike is much easier.

The same is true for enlisting the support of other unions for the strike. Requests for strike leaders to appear at union meetings should be sent to all the unions in the area. These unions should be asked to support the strike both financially and physically by joining our mass picket lines. Again, these requests will be much more successful if the Local has a policy of maintaining good relations with other unions in the area and coming to their aid when they need help.

Finally, community support can be a powerful aid in winning the Union's demands. During the course of the dispute, the Company will probably use local newspapers, radio, and TV to set the community against the strikers. But it can work the other way, too: winning community sympathy and support can put powerful pressure on the Company to meet the strikers' demands.

Public opinion cannot usually be won overnight. A Local with a record of community involvement — and an active Publicity Committee working to make that involvement known — has a much better chance of winning over public opinion when the time to strike does come.

Strikes are not everyday events. But the capability to conduct one should shape how a Local operates both in the short term and for the long haul. In the pages that follow, suggestions are made for both short-term and long-term preparations in each area. Read them carefully, compare them with you Local's current practice, and put them into effect where needed.

Note: Not all sections of the strike guide have been put online yet. If you are a member of a UE Local, this guide is reproduced in its entirety in the UE Leadership Guide chapter on strikes. Otherwise, please sign up for the UE Action Net on the right side of this page (or bottom on mobile) so you can be kept informed as we complete the online version.

The Strike Machinery

The regular leadership of the Local Union — the Officers, Executive Board, Negotiating Committee and Steward's Council — should constitute the leadership of the strike. In an amalgamated Local, the strike organization should be set up on a shop basis with appropriate support and guidance from the Local.

All Committees should be set up and read to operate before the strike begins. Heads (Chairs) for each Committee, when and where the Committees will meet, what their responsibilities are, and how their work is to be coordinated, must be decided beforehand by the Executive Board. Committees will vary in size according to the size of the plant and the nature of their work. In setting up these Committees, special attention should be given to assign members to the work they are best equipped to do.

In selecting Committee Chairs, care should be taken that they can devote all their time to the Committee without being overloaded with other responsibilities. Bear in mind that the success of their Committee may depend on their tact and knowledge of the problems.

Assistant Committee Chairs should also be named to take over in the absence of the regular Chair.

During the strike, it often happens that natural leaders arise outside the formal strike leadership. They should be encouraged and their efforts given recognition. It will increase the leadership depth in the Local.

Suggested Committees are as follows:

- General Strike Committee

- Picketing Committee

- Financial Support Committee

- Publicity Committee

- Fundraising Committee

- Strike Kitchen Committee

- Strike Headquarters Committee

- Education and Entertainment Committee

Each is discussed in detail in the pages that follow. (though not all of those pages have been posted yet)

General Strike Committee

The Local Officers, Executive Board, Negotiating Committee, and Chairs of Committees form the General Strike Committee. This Committee is in full charge of the strike and is responsible to the Local membership. Its members should be available to meet at any time.

The General Strike Committee instructs each Committee in its duties when each is first set up. It hears reports from ad gives direction to all Committees regularly. The jobs of the General Strike Committee are as follows:

- Meet regularly.

- Set up all Committees and assign their members.

- Keep in close touch with negotiations and see that all developments are reported to the membership.

- Maintain contact with the UE National Office.

- Approve the use of the phone tree when needed.

- Approve all strike publicity, both to members and the general public.

- See that Strike Bulletins are issued regularly containing information about negotiations, instructions to the strikers, and other pertinent news.

- Schedule regular strike meetings of the membership.

- Keep control of all strike finances; keep careful accounting of all funds raised by the Fundraising Committee.

- Keep adequate records of decisions made and acted upon by all Committees during the strike.

- Take all other measures necessary for properly conducting a winning strike.

In addition, the General Strike Committee should be directly responsible for two areas throughout the strike. First, it should budget available strike funds and continually revise this budget as needed. Second, it should directly handle all legal problems that might arise.

Notifying the National Office

As soon as it is clear that a strike may be pending, the UE National Office should be notified. This will send a yellow light to the National Office, telling it to get ready to assist you. Likewise, the National Office should be notified when and if the strike is called — giving it the green light to begin helping with legal, financial, and manpower support.

A National Strike Defense Fund was set up by an amendment to the UE Constitution in 1970. Under it, the National Office makes weekly lump sum payments to Locals beginning in the third week of the strike; based on the number of UE members on strike. The amount is set by the Union's General Executive Board and is periodically adjusted.

But the National Office has to be notified first. And during the strike, a strike expense report has to be submitted by the Local each week so that it can continue receiving money from the National Office.

Budgeting

Article 18 of the UE Constitution requires Locals to set up their own Strike Defense Funds. Although the National Fund is helpful, the major source of money is the Local's own Fund. Other money can be gotten through the efforts of a Fundraising Committee. Working with that Committee and the National Office, an estimate of funds available should be made and then revised, if necessary, during the strike.

The major strike expenditures are as follows:

- Food assistance to strikers, either through food distributions or credits toward food purchases.

- Utilities and rent/mortgage assistance to strikers.

- Transportation assistance.

- Operation of a Strike Kitchen, if any.

- Printing expenses for materials distributed to members.

- Radio or newspaper advertising, if any.

- Strike headquarters expenses, if it is located other than in the Local's offices.

- Legal expenses.

- Other expenses.

Some of these items will be very difficult to estimate at first, but that should be done well before the strike begins. As the strike continues, the estimates will become more realistic and can be revised.

Each expenditure should be estimated on the basis of a weekly average. Dividing the estimated total expenditure for a week into the available funds will tell how long the money can be expected to last.

Spreadsheet programs, such as Excel, Numbers, or Google Sheets, can be very useful in making and changing budget estimates.

Budgeting and the Local's financial situation in general should be kept strictly confidential within the General Strike Committee for the duration of the strike. After the strike is over, a full accounting should be made to the membership.

Legal Problems

All legal problems arising from the strike must be handled directly by the General Strike Committee working with the UE National Office. Legal problems are generally of two types.

Companies commonly get court injunctions to stop some strike activity, usually mass picketing. Fighting an injunction means going to court (See Appendix A, “Court Injunctions” [1]). After discussion with the National Office, the Committee will have to determine what it wants to do, given the circumstances.

The second legal problem — bailing out those arrested during the strike — is more complicated and is explained in Appendix B, “Bail in Strike Situations.” (Note: Appendix B is not online yet) Here, the Committee has to weigh several factors: the hardship to the strikers involved, the cost of the bail, the means to raise it, and the publicity that it generates.

Outreach and Publicity

The Publicity Committee is vital to the winning of a strike and can make the work of every other Committee easier and more effective.

The Publicity Committee works under the close supervision of the General Strike Committee. It is responsible for the preparation and distribution of information to both the Local's membership and to the general public through:

- Strike bulletins regularly distributed to members.

- Letters to the membership.

- Special leaflets to members or to the public.

- News releases to radio, TV, and the press.

- Radio spot announcements.

- Newspaper ads.

- Appearances on radio and TV programs.

The National Office has people available to help in setting up spot announcements, schedules, wording, newspaper ads, and radio and television appearances. The bulk of the work, however, must be done by the Local Committee. The daily strike bulletins, news releases, letters to members, and leaflets must be prepared locally.

If there is no Publicity Committee, this work will inevitably fall to the Officers and other strike leaders. This gives them an extra burden; even worse, it often results in this vital work being neglected.

Those who work on the Publicity Committee should not be expected to put in time on other strike committees. Doing a good job won't leave them time for anything else — and a good job by this Committee is vital to the success of the strike.

The need to get the Union's position to the public and information to striking members cannot be over-emphasized. But those are two very different audiences. Each is discussed below separately.

Some General Rules

From a publicity angle, a strike is like a conversation between the Union and the Company with the membership and the general public as the audience. The Publicity Committee holds up the Union end of the conversation. That means figuring out when and how to answer and when to keep silent.

There is a trick to it: always put yourself in your audience's shoes. What do they want and need to know at each point in the conversation? What do they already know? Explain what you think they will need to have explained.

Do not assume that the audience has followed every word of the conversation — not even the membership. This is even truer of the general public who are drifting in and out, catching only snatches of the conversation at best.

So: Keep it basic. Be clear. And be direct.

Communicating with the Membership

The tension and pressure of a strike breed rumors and false information. This grows each day as the strike continues.

Companies know this and often try to exploit it. If a striker is misinformed or does not understand the basic issues or the Union's actions, his or her determination weakens. Even worse, they might begin to feel abandoned or "sold out" by the Union. On the other hand, the well-informed worker with a good understanding of the issues and the progress of the negotiations will be the most effective striker. Even better, they will be a rallying point for their co-workers.

These are some things members might want and need to know:

- What is happening in negotiations. Keeping people fully informed during negotiations will greatly simplify things later, when the contract has to be explained so the Local can vote on it.

- Important changes in the Union's negotiating position, explanations of why such changes were made, and — as clearly and directly as possible — how it affects them.

- How to get help (financial and otherwise) from the Local or other agencies.

- The Union's answer to stories about the strike that members might have seen in the newspapers or on TV or heard over the radio.

- Information about available jobs.

- How other people in the Local are doing.

- Times and places of strike meetings and contract votes.

It is very important to correct misinformation early. It is even better to anticipate how events might be misunderstood and to put them in the right light before things get off track.

Communicating with the General Public

Winning over publicity opinion to the side of the strikers can be an enormous plus. This is difficult, however, for two basic reasons. First, reaching the public means using the media — radio, TV, newspapers — and the media may be indifferent or even hostile.

Second, public attitudes towards unions and strikes are confused and many people understand very little about either. Some people are anti-union; the best efforts of a Publicity Committee will not change their minds. Others in the general public are pro-union and will be sympathetic. The real audience to reach is the people in between. People who haven't made up their minds because they don't understand why workers need unions or why workers sometimes have to strike.

Here's the catch: the people in between, the ones you are trying to reach, get hit over the head every day by the employer's propaganda machine. In other words, certain ideas and attitudes about workers and their unions are kept floating around out there. People don't necessarily believe them, but if the Local's publicity ignores them — or even worse, unwittingly reinforces them — people will begin to see things the way the Company wants them to.

Here are some pitfalls to avoid:

Hard as it is to believe, the Company may try to picture itself as a little David fighting a Union Goliath. The know that Americans generally love the underdog and so they try to paint unions as huge, powerful organizations that trample over people to get what they want.

Don't let them get away with it. Let people know that the decision to strike was made democratically, by the UE workers involved, by people in their community — not off in some union office somewhere. In fact, it is usually the Company's decisions that are made in some faraway office.

The Company may try to paint itself as a respectable member of the community and the Union as a bunch of outsiders. It is very important for people to see the Union as really nothing more than a group of their own neighbors, ordinary people who are struggling to get their fair share. Or, ways might be shown in which the Company is not being the "good neighbor" it would have people believe it is. Many companies pay little or no taxes — especially locally. Others freely pollute the environment.

The Company may make noises about closing the plant, not only to frighten striking workers, but also to frighten the community and local political leaders. Especially if they make these threats quietly and behind the scenes, expose their game to the public. They are being disloyal to a community that has supported and helped them; the community has given all kinds of breaks to let them make money here, and now they are talking about walking away. Another way to handle it is that they are holding the plant — and the community — as hostages to get the workers to give in. That's terrorism.

The Company may try to show the strike as being caused by greedy workers. It is very important to get the public to understand how modest and reasonable the Union's demands are — in terms they can understand. For example, a pay increase of $20 a week for the average worker. Or, an improved health care package because last year a worker's daughter needed an operation and the family has to take out a second mortgage to pay for it — and let the reporters interview the family involved.

The Company may try to paint the strikers as prone toward violence and may even arrange incidents to provoke it. Historically, violence has usually turned public opinion against striking workers; that is why some companies try to use it. Should such incidents occur, it should be made clear to the public that the Union does not condone violence. If Union members have been injured, point that out. In the case of a provoked incident, the Union should publicly announce that it is going to take aggressive legal action.

Don't let the Company confuse the public by making the issues too complicated for them to understand. Remember, most people understand very little about contracts and strike issues. Don't let the Company pull you into a public "pissing contest" over whether their offer really means 50 cents an hour or just 40 cents. If the Company begins puffing clouds of complication, keep pushing the issues as simple matters of fairness and justice. This will not convince the Company; it may convince the public.

One last point. Do not call the Company stupid, a bunch of fools, or greedy monsters however true that might be. It is a strange thing but true that the more extreme the Company's conduct, the harder it will be to convince people of what is going on. If the Company does something particularly outrageous, or grossly unfair, or blatantly illegal, do not assume the public will recognize it as such, Such things must be even more carefully and more thoroughly explained than usual if they are to have impact.

Community Support

If the Local has no Community Relations Committee, a special Subcommittee of the Publicity Committee should be responsible for organizing support outside the Local.

Suggested contacts for this Committee:

- Locals of all the other unions in the area.

- The Mayor.

- The City Council.

- Local Congresspeople.

- Prominent citizens.

- Community organizations (religious, fraternal, etc.).

- Neighbors — by house-to-house canvassing.

Those who respond favorably to the committee's presentation should be asked to support the Union in any way that may be appropriate; for example, by writing to the company urging it to settle the strike, passing a resolution in support of the union, or providing financial or material assistance.

The Subcommittee should contact everyone, including those who in the pas might have had a negative attitude toward UE or the labor movement in general. This is especially true for elected officials for three reasons:

- Sometimes, people do change their minds.

- If you don't contact them, they can weasel out by saying, "Oh, nobody got in touch with me."

- If they were getting ready to come out against the strike, sending a delegation just might make them think twice about it.

This Subcommittee should arrange for distribution of special strike literature in downtown areas and neighborhoods. It should organize community meetings to which the townspeople are invited.

Fundraising Committee

Raising money to support the strike is one of the most important strike activities. A Fundraising Committee should include people who are articulate enough to go before different kinds of audiences and appeal for funds.

This is not as hard as it may seem. A surprising number of people will welcome the chance to show their solidarity with striking workers by contributing money. (Often because they can easily imagine themselves in the strikers' position.)

Some suggested methods of raising funds are:

- Well before the start of negotiations, build up the Local Strike Fund through a special Local assessment.

- Organize raffles, benefit shows and dances.

- After the strike starts, organize plant gate collections at all shops in the area.

- Make appeals at meetings of unions and other organizations in the area.

All fund raised must be reported to the General Strike Committee.

UE Policy on Strike Assistance

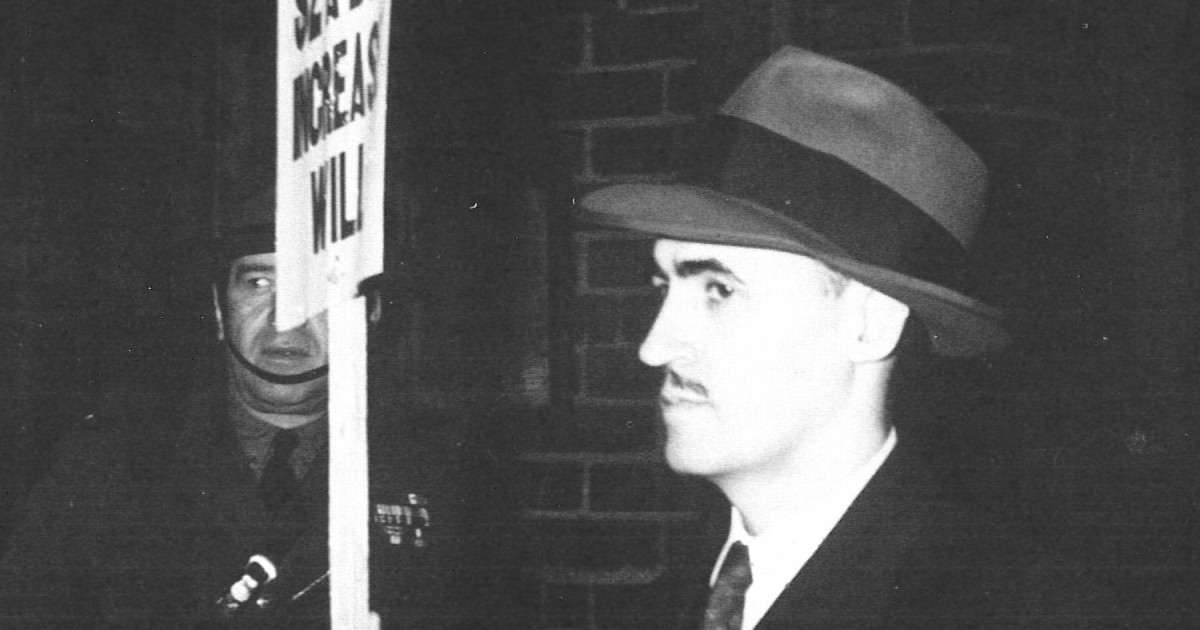

James Matles was UE's first Director of Organization. John L. Lewis, the legendary President of the United Mine Workers, once called him the best field organizer he had ever seen.

At UE's 33rd Annual Convention in 1968, Matles explained the reasons behind UE's policy on strike assistance. Drawing on 35 years of organizing experience, he made the following remarks:

...I want to tell you that the subject matter we are talking about right now is probably one of the most fundamental trade union problems facing the American trade union movement.

The real meaning of working people striking has been protituted and corrupted during the past several years. Somehow, the idea has gotten around this land among working people that there is a painless way of striking. A striker doesn't have to picket anymore — he just comes down to the Union to get a weekly check since he is not getting it from his boss. If the Union doesn't give him a check, it's like the company not paying on pay day.

Before the 1967 auto strike was called, everybody kept speculating on what the big strategy was going to be and which of the three companies was going to be struck first. The reason General Motors was not struck was no big strategy. There were 300,000 GM workers and it would cost $6 million each week. The reason Ford was struck was because it was going to cost less money.

The 1967 Ford strike lasted 44 days. When the strike was only four weeks old, the UAW had to call an emergency Convention to pass a $5.00 a week assessment on the entire UAW membership for the duration of the strike.

Each Ford striker got a grand total of about $125 during the 44-day strike.

Thousands of Ford workers got other jobs and after work, once a week, they would come down to the picket line in order to collect their weekly check for $20 to $25 from the Union. Why did they demand their check when they had another job?

The answer is simple.

They were doing the Union a favor by going out on strike. This is what I meant when I said the proud strike tradition of the American trade union movement has been prostituted.

I have been brought up in an altogether different trade union tradition. When the Union releases a striker to get another job during the strike, he is duty-bound to make a substantial contribution to help those who are carrying the load on the picket line.

Can anyone tell me that when a member of our Union goes out for ten, fifteen, or twenty week on strike, as many of our people have done, and he loses $1,500 to $3,000 in pay, that the $20 a week solves his problems in any real way? Or, if the company opens the gate and starts a back-to-work movement to break the strike, does anyone believe that giving each striker $20 a week, no matter what his real needs are, will make the difference between striking and scabbing?

The United Mine Workers of America have never paid out strike benefits of so many dollars a week to anybody who will to the Union a favor by going out on strike.

I remember one of the first discussions [first UE Secretary-Treasurer Julius] Emspak and I had with John L. Lewis in the early days when we had out strikes and we were worried and concerned. He took us in hand and said, "The miner can live on ten dollars a day, when when we had to be can live ten days on a dollar."

That is the way miners were brought up. There were no scabs in those mines and if somebody tried, they didn't give the miners $20 apiece, they gave them a shotgun apiece.

I remember during the Westinghouse strike in 1947 we were sitting in negotiations in Pittsburgh during the fifteenth or sixteenth week of the strike and the company told us that the Sharon Westinghouse plant was ready to break ranks and go back. We recessed the negotiations for the afternoon and called up our Strike Committee in Sharon and asked them to call a meeting for that night at the high school. When our committee arrived at Sharon there were 2,500 strikers packed into that high school.

It was one helluva rip-roaring meeting — it looked like that strike would go on forever.

When the meeting was over, an elderly man and his wife came over to me on the platform. He said, "Son, when you came into this hall, you looked mighty worried. What were you worried about?"

"Well, the company told us that you fellows were about ready to break ranks," I told him.

"Son, we elected you to negotiate in Pittsburgh and if you do your job half as good as we do ours here, we will come out all right. Go back and do your job."

The national strike against Westinghouse lasted 17 weeks. Every striker got the help he needed so that the family was assured of clothing, food, shelter, heat, light, and other necessities of life.

But we don't pay a striker because he was striking as a favor to the Union.

In 1955, we had a second national strike in Westinghouse that lasted four and one-half months, but our Local 107 at the Westinghouse Lester plant continued the strike over its local supplemental for a total of 299 days. Six thousand production and salaried workers kept the plant shut for 299 days without a single scab.

To feed and clothe and shelter those strikers took the combined efforts of the striker themselves, the UE Locals all over the country and the International Union. This was one of the epic struggles in the history of the labor movement and it wasn't done on the basis of twenty-buck-a-week handouts whether a striker needed it or not.

You hear the two delegated from Local 274, Greenfield Tap & Die, report on their thirteen-week strike that just ended. Maybe they spent as much money as would have been spent if they gave everybody $15 to $20 a week. They didn't do it that way. Any striker who needed help had to appear before a committee of the strikers and had to say what his problem was and he got the help that he needed. The Relief Committee made sure that he was not evicted from his home, that the gas and light were not shut off, that there was food on the table, that a pair of shoes was gotten for the kid — if the kid needed a pair of shoes — but he had to stay on the picket line and be active in the strike.

One man may have gotten during the strike five times more help than somebody else, and the third one may not have gotten anything else at all, but that is the way to run a strike — that is the way to run it.

You don't run a strike on a slot machine basis.

The Machinists Union is another one of the outfits that has weekly strike benefits. About five to ten years ago, they got a special 50 cents per capita to set up the Fun. They got another 50 cents for the same purpose and now at this Convention they are asking for another $1.00 increase in per capita for the Strike Fund.

The Machinists Union has been using the Strike Fund as a means of exercising dictatorial control over the Locals. Time and again, the International refused to authorize a strike after the membership overwhelmingly voted in favor of striking. When the International refuses to authorize a strike, it means no strike benefits. In those cases where the International finally agrees to authorize a strike, it has absolute control to decide on what conditions the strike is to end.

Time and again, the rank and file turned down the terms of a strike made by the International, but the membership was forced back to work when the International cut off the payment of weekly strike benefits.

During my years in the labor movement, I was shop steward, I was secretary of a Local Union, I was an organizer of a Local Union — I have had my share of strikes. We hear some super-militants get up on the floor and clamor for a strike a minute. We used to test their militancy by making them show what sacrifices they would make in preparation for a strike.

Before the last GE and Westinghouse negotiations we said to our people, "Don't buy anything on installment credit right now. If you have any overtime, put the damn money aside — you will need it. Don't make any new financial commitments."

Furthermore, what a Local Union should do before negotiations start and while people are still working, if they are serious about taking on the company, they should be willing to substantially build up the Local Strike Fund; they should help themselves before they ask other Locals to help them. We have had Local Unions that had each member put in a day's pay or an hour's pay every week for eight weeks, and you build up your Local Strike Fund.

The International always puts in its share. We put in money consistent with what we can.

I understand the IUE is talking about a great idea. They are going to take GE and Westinghouse on next year by setting up $12 a week strike benefits by increasing the per capita and dues by a dollar a month.

GE and Westinghouse are just shivering in their boots right now. This is going to give GE sleepless nights. If GE and Westinghouse go out on strike, even this great sum of $12 a week will break the IUE strike fund in three weeks.

What is going to decide the outcome in GE and Westinghouse is whether we can get unity; whether we can get it in the way we had it in '46; whether we have a policy of fighting the company; or whether they are going to depend on [AFL-CIO President] George Meany, [U.S. President] Lyndon B. Johnson, or [U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert] McNamara to help them out. If they do, they will drown and $12 a week won't save them.

So, we say to you, "Yes, have some serious discussions on this question." We have got to have more funds in our Local Strike Funds. Yes, we need more in the District Strike Funds. We are going to have a little more in the National Strike Fund, the per capita is going up on December 1st — 35 cents. Ten cents of that is going into the Defense Fund, which will give us a little more money to help Locals in their strikes.

We are not going to create any illusions among our people. We have to try to handle the strikes in the way the labor movement handled them for generations. Our people have got to know, in the first place, that a strike means sacrifice. Second ,the Union will see that nobody goes hungry and everyone has a roof over his head. This our Union has always done.

I want to wind up with a little story to illustrate a fact about scabs that every strike leader knows. There are those who think that most of those who scab against their fellow workers do so because they are in worse economic straits. This is not so. For every scab who crosses a picket line because he is in great financial trouble, there are ten others doing so because they are money-hungry, selfish, and have never learned the meaning of trade unionism and working-class solidarity.

The 1955 UE Westinghouse strike started in October and lasted until April of 1956. On the day after Christmas, I went out on the picket line in Nuttall with my old friend, George Gibbs, the Local President, who many of you know.

On that day, the first guy crossed the line. He was a bachelor, 62 years old, with 35 years' service. He lived with his mother for many years. He was a guy who could never get enough overtime and on weekends, he tended bar near the plant.

During all the years with the Company, he invested his money in Westinghouse stock. Do you know how much his stock was worth? I'll tell you; it was worth sixty thousand dollars — $60,000 — and he was the first s.o.b. to cross that line.

He crossed it only once.

Appendix A: Injunctions

The injunction is the employers’ favorite strike-breaking weapon. Its main purpose is to undermine support for the strike and demoralize the picketers, paving the way for a back-to-work movement. Experience has shown that once an injunction is issued and workers absorb its impact without weakening, it is of much less usefulness as a strike-breaking weapon.

An injunction cannot break a strong and effective strike, but it can considerably damage one which is weak and poorly organized.

If an injunction is threatened or impending, contact the National Office immediately.

Technically, there is a Federal law which prohibits the issuance of injunctions in labor disputes. In practice, companies can often overcome this by showing that strikers are doing any one of a number of things, such as blocking traffic or engaging in violence. The usual injunction (or restraining order) is against “mass picketing” — that is, limiting the number of picketers at each plant gate.

The legal process for issuing an injunction is a bit complicated. On the basis of evidence from the company lawyer, the court will set a hearing date for issuing an injunction, usually seven to ten days later; at that time, the union gets its day in court.

But the company’s lawyer might also ask the judge to issue a “temporary restraining order” in the meantime. It’s up to the judge, but if he agrees, the restraining order will prevent the union from doing certain things until the injunction hearing. Although an injunction is legally more powerful, a temporary restraining order can have the same effect in practice — especially if the injunction hearing is delayed.

To obtain an injunction, companies sometimes provoke incidents on the picket line through scabs and hired finks. Video tape or film is used to record these manufactured incidents (for use in court as evidence of the need for the injunction). In this situation, picketers must bear in mind that they have a Constitutional right to picket peacefully and to persuade would-be scabs not to go into the plant.